Contents:

Management of end of life symptoms

Whenever a Parkinson’s patient enters the lasts days or weeks of life, all medications should be reviewed and rationalised. It is imperative that the main dopaminergic drugs (outlined below) are not abruptly stopped. Specialist opinion should be sought early to assist with medication review. It is likely that specialists will already have reduced the overall dose of PD medications as dopamine responsiveness wanes and side effects become more problematic.

Rigidity and bradykinesia can be painful, disabling and distressing, limiting even basic movement and function such as swallowing. Sudden withdrawal of levodopa or dopamine agonists can theoretically precipitate the rare parkinsonism-hyperpyrexia syndrome, presenting with hyperthermia and rigidity. In addition, abruptly stopping dopamine agonists can cause withdrawal syndrome, including anxiety, panic attacks, sweating, and drug craving.

Patients with PD often have complex medication regimens. The most important medications to continue are levodopa preparations (Co-careldopa or Co-beneldopa) and/or dopamine agonists (Ropinirole, Pramipexole, Rotigotine, Apomorphine).

If a patient is struggling with solid tablets, some medication (with the exception of modified-release preparations) may be crushed and dispersed in water:

- Standard-release Co-careldopa tablets disperse in water;

- Co-beneldopa capsules can be switched to dispersible Madopar® tablets;

- Ropinirole and Pramipexole, which are often prescribed in modified-release formulation, should be switched to standard/immediate-release forms, which can be dispersed in water

Switching To Orodispersible Formulations and Switching To A Transdermal Rotigotine Patch offer more specific advice and dosage calculations.

If the patient is predicted to be in their last days of life, then MAO-B inhibitors (Rasagiline, selegiline and safinamide), COMT inhibitors (entacapone and opicapone) and amantadine can be confidently ‘de-prescribed’. Some of these drugs may be contributing to unnecessary polypharmacy and agitation in the dying patient (see Terminal Agitation and Delirium below).

When the oral route is no longer available or desired, the relevant medications can be converted to a transdermal Rotigotine patch. See Switching To A Transdermal Rotigotine Patch for conversion tables.

There are two Online Parkinson’s Calculators in popular use; PDMedCalc (pdmedcalc.co.uk) and OPTIMAL (parkinsonscalculator.com)*. Both use different formulas to calculate conversions from Levodopa to topical Rotigotine. There can be significant differences, especially when the total levodopa dose is less than 500mg with ‘PDMedCalc’ typically generating lower dose conversions. The current ‘OPTIMAL’ calculator needs updating and issues have been identified with intra-calculator variability and thus its use is not recommended by our team (nor UKCA marked). We strongly advise clinicians to use the tables in Switching To A Transdermal Rotigotine Patch but to be mindful of the need to reduce doses in those with cognitive impairment or naive to dopamine agonists.

A proactive advance care plan should be in place to manage dysphagia. This should ideally be discussed with the patient and their advocates prior to the end of life.

In the last days (or weeks) of life, the patient with PD is unlikely to be able to swallow effectively or meet their nutritional needs. In these circumstances:

Placement of a nasogastric tube (NGT) is rarely appropriate;

The use of intravenous or subcutaneous fluids is unlikely to add to comfort and may lead to problems such as fluid overload and increased chest secretions;

Good oral mouth care is the best approach to manage a dry mouth.

In the uncommon scenario where a patient already has a PEG tube, continue to use this route for medication. However, consideration should be given to reducing PEG feed due to aspiration risk, especially in someone who is deeply unrousable. In the rare instance of a PEG-J tube being in place for DuoDopa administration (see Duodopa Intestinal Gel below), this is NOT to be used for enteral feeding.

There is a wealth of guidance on clinically assisted hydration and nutrition from the GMC, a joint publication from the RCP and BMA, and West Midlands Palliative Care Guidelines.

Waning dopamine responsiveness is common in advanced disease and can result in marked rigidity. If a patient with PD is becoming more rigid at the end of life, first ensure they are receiving their medications at the correct times. Additionally, rule out constipation, which delays absorption in the small intestine.

Increasing the dose of dopaminergic therapies is unlikely to be helpful and may cause delirium and agitation. Midazolam can be used effectively for agitation caused by rigidity (see Terminal Agitation and Delirium below), and morphine can be used for pain caused by rigidity (see Pain below).

Pain is often under-recognised and should be proactively assessed and treated. Address the cause of pain and treat first where possible: consider common causes such as rigidity, urinary retention and constipation.

Pain can be a complex symptom to assess and may not relate directly to Parkinson’s. In advanced PD, be mindful that non-specific and poorly localised pain can be seen as part of non-motor fluctuations.

In the last few days of life, the best approach is to maintain previous doses of dopaminergic medication rather than acutely increase. If there is any doubt, specialist opinion should be sought.

Once PD medications are optimized, other analgesics can be used. If the patient is opioid-naive and creatinine clearance is above 30mL/min, consider Morphine Sulfate 2.5mg S/C PRN in the first instance. Palliative care guidelines offer alternatives for use in reduced renal function: see section: renal failure.

Look for causes of nausea and vomiting, including medications and constipation (a common symptom in PD), and treat accordingly.

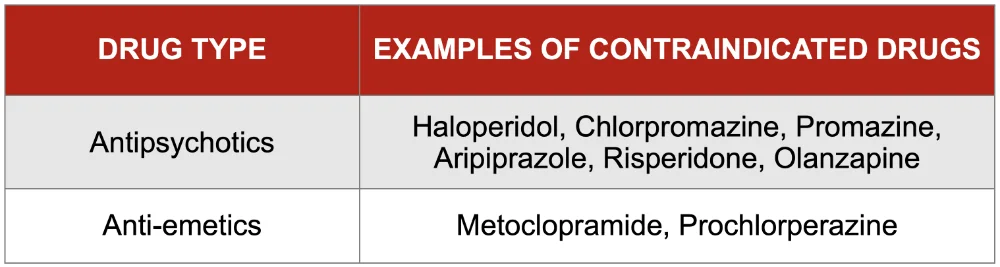

High-quality data to guide treatment of nausea is lacking. However, medications which have a strong blockade of central dopamine receptors should be avoided: never prescribe metoclopramide, haloperidol or prochlorperazine.

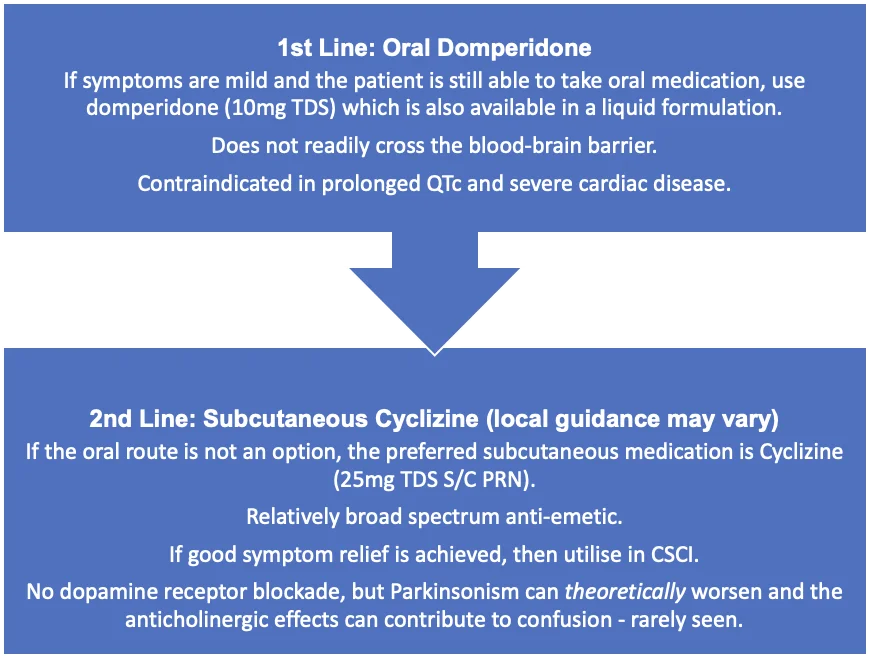

The following flow chart suggests a stepwise approach to prescribing; note local guidance may vary when choosing an antiemetic for subcutaneous administration.

Ondansetron can be used but is less likely to be effective in the palliative setting and may contribute to constipation. Ondansetron is contraindicated in patients receiving Apomorphine due to the risk of profound hypotension and drowsiness.

It is worth noting that the risks and side-effects of medications, versus their benefits, may change in last days of life. Levomepromazine is usually contraindicated in PD due to high affinity for dopamine receptors but may be considered in extreme cases if no other therapeutic strategies are effective (e.g. intractable nausea and vomiting) – this must be discussed with a PD or palliative specialist.

Upper airway secretions at end of life are common – at least 70% of patients are affected in most palliative settings and perhaps more in PD due to swallowing problems. Witnessing noisy and bubbly breathing is often more distressing for those at the bedside than the patient, therefore explanation is important for relatives and carers. Changing the patient’s position (if practically possible) may help postural drainage. For example, ‘high side lying’ with the patient positioned upright and their head tilted to the side.

If secretions are problematic despite conservative measures, Hyoscine Butylbromide can be used as in most other end-of-life situations. Prescribe Hyoscine Butylbromide 20mg S/C PRN, but have a low threshold for starting a CSCI early in the development of secretions. A typical starting dose of Hyoscine Butylbromide in a CSCI is 60mg/24 hours.

It should be noted that Hyoscine Butylbromide and Cyclizine should not be mixed in the same syringe driver, as the latter may crystallise. Therefore, if both anti-secretory and antiemetic drugs are required in CSCI, it is recommended to use Glycopyrronium with Cyclizine, negating the need for two syringe drivers. A typical starting dose of Glycopyrronium via CSCI is 600 micrograms/24 hours.

Glycopyrronium and Hyoscine Butylbromide do not cross the blood brain barrier and are unlikely to cause side effects such as drowsiness and confusion.

First, address potentially reversible causes such as constipation, urinary retention or pain.

A number of specific drugs are contraindicated in Parkinson’s due to blockade of central dopamine receptors which can worsen Parkinsonism and contribute to agitation. Review the drug chart to ensure these are not prescribed.

If reversible causes have been addressed, prescribe PRN Midazolam 2.5mg – 5mg S/C PRN hourly. If 3 or more doses are used in a 24 hour period consider starting a CSCI. Consult palliative care guidelines for dose adjustment in renal impairment: Renal Failure.

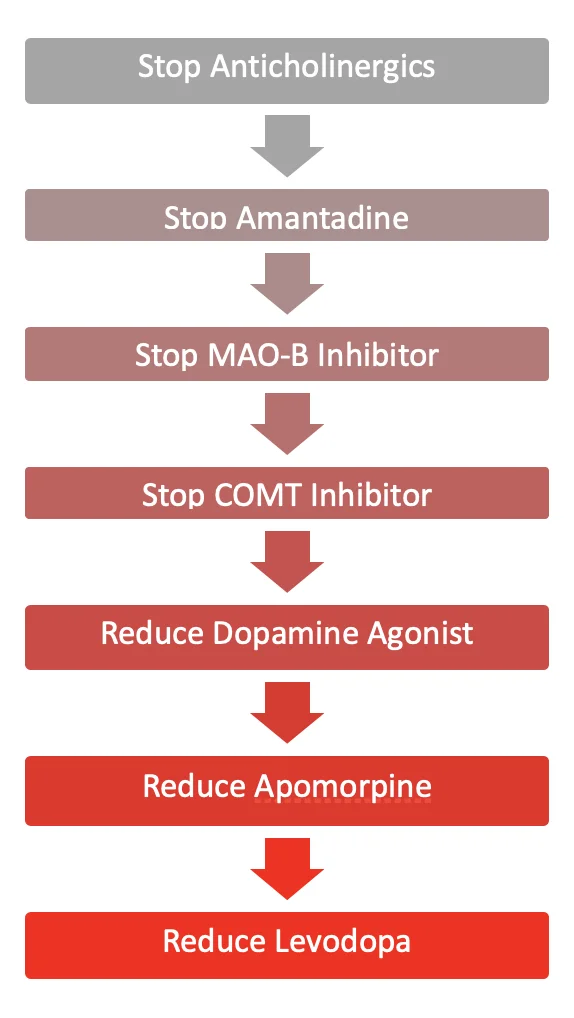

A reduction in dopaminergic therapies might be needed in the event of agitation and hallucinations. In such cases, there will be a ‘trade-off’ between increased rigidity and the relief of an agitated delirium. This should be discussed with a PD specialist.

A suggested stepwise approach to review dopaminergic and anticholinergic therapies is outlined below, considering efficacy and side effect profiles. In most settings, PD medications should have been rationalised by a specialist in the palliative phase before the patient is actively dying.

Management of end of life symptoms

General Principles

Whenever a Parkinson’s patient enters the lasts days or weeks of life, all medications should be reviewed and rationalised. It is imperative that the main dopaminergic drugs (outlined below) are not abruptly stopped. Specialist opinion should be sought early to assist with medication review. It is likely that specialists will already have reduced the overall dose of PD medications as dopamine responsiveness wanes and side effects become more problematic.

Rigidity and bradykinesia can be painful, disabling and distressing, limiting even basic movement and function such as swallowing. Sudden withdrawal of levodopa or dopamine agonists can theoretically precipitate the rare parkinsonism-hyperpyrexia syndrome, presenting with hyperthermia and rigidity. In addition, abruptly stopping dopamine agonists can cause withdrawal syndrome, including anxiety, panic attacks, sweating, and drug craving.

Medication Management

Patients with PD often have complex medication regimens. The most important medications to continue are levodopa preparations (Co-careldopa or Co-beneldopa) and/or dopamine agonists (Ropinirole, Pramipexole, Rotigotine, Apomorphine).

If a patient is struggling with solid tablets, some medication (with the exception of modified-release preparations) may be crushed and dispersed in water:

Standard-release Co-careldopa tablets disperse in water;

Co-beneldopa capsules can be switched to dispersible Madopar® tablets;

Ropinirole and Pramipexole, which are often prescribed in modified-release formulation, should be switched to standard/immediate-release forms, which can be dispersed in water

Appendix 1 and Appendix 2 offer more specific advice and dosage calculations.

If the patient is predicted to be in their last days of life, then MAO-B inhibitors (Rasagiline, selegiline and safinamide), COMT inhibitors (entacapone and opicapone) and amantadine can be confidently ‘de-prescribed’. Some of these drugs may be contributing to unnecessary polypharmacy and agitation in the dying patient (see section 3.8).

When the oral route is no longer available or desired, the relevant medications can be converted to a transdermal Rotigotine patch. See Appendix 2 for conversion tables.

There are two Online Parkinson’s Calculators in popular use; PDMedCalc (pdmedcalc.co.uk) and OPTIMAL (parkinsonscalculator.com)*. Both use different formulas to calculate conversions from Levodopa to topical Rotigotine. There can be significant differences, especially when the total levodopa dose is less than 500mg with ‘PDMedCalc’ typically generating lower dose conversions. The current ‘OPTIMAL’ calculator needs updating and issues have been identified with intra-calculator variability and thus its use is not recommended by our team (nor UKCA marked). We strongly advise clinicians to use the tables in Appendix 2 but to be mindful of the need to reduce doses in those with cognitive impairment or naive to dopamine agonists.

Nutrition and Hydration

A proactive advance care plan should be in place to manage dysphagia. This should ideally be discussed with the patient and their advocates prior to the end of life.

In the last days (or weeks) of life, the patient with PD is unlikely to be able to swallow effectively or meet their nutritional needs. In these circumstances:

Placement of a nasogastric tube (NGT) is rarely appropriate;

The use of intravenous or subcutaneous fluids is unlikely to add to comfort and may lead to problems such as fluid overload and increased chest secretions;

Good oral mouth care is the best approach to manage a dry mouth.

In the uncommon scenario where a patient already has a PEG tube, continue to use this route for medication. However, consideration should be given to reducing PEG feed due to aspiration risk, especially in someone who is deeply unrousable. In the rare instance of a PEG-J tube being in place for DuoDopa administration (see Section 4.2), this is NOT to be used for enteral feeding.

There is a wealth of guidance on clinically assisted hydration and nutrition from the GMC, a joint publication from the RCP and BMA, and West Midlands Palliative Care Guidelines.

Disclaimer

These Guidelines are intended for use by healthcare professionals and the expectation is that they will use clinical judgement, medical, and nursing knowledge in applying the general principles and recommendations contained within. They are not meant to replace the many available texts on the subject of palliative care.

Some of the management strategies describe the use of drugs outside their licensed indications. They are, however, established and accepted good practice. Please refer to the current BNF for further guidance.

Whilst SPAGG takes every care to compile accurate information , we cannot guarantee its correctness and completeness, and it is subject to change. We do not accept responsibility for any loss, damage or expense resulting from the use of this information.